Christmas and Santa Claus are eternally entwined in western culture. Think of a pile of gifts beneath the tree on Christmas morning and you doubtless imagine a jolly overweight man (we’re not fat-shaming, Santa seems perfectly happy with his physique) shimmying down a chimney and distributing the contents of a giant black bag.

The red suit, long white beard and jolly ho-ho-hoing that we associate with jolly old Saint Nick is not shared throughout the world, however. Many cultures have their own idea of how Santa looks and behaves – for example, in Japan he has been varying portrayed as a samurai warrior, a robot and a cat, while in China he is rarely seen without a saxophone at his lips.

Countless different nations have their own interpretation of the myth, however, and not all of them are entirely wholesome. Lets take a look at some of the alternative Santa folklore throughout the world.

Sinterklaas

Let’s start at the beginning – where does the traditional Santa legend stem from?

By Michell Zappa] – [1], CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

The short answer is The Netherlands. Dutch settlers in New York brought the folk tale of Sinterklaas with them – including key components such as eight flying reindeer, entering homes through the chimney, setting up a workshop in the North Pole and – perhaps most importantly – clad in red and white.

That’s right, the fabled conspiracy theory that Coca-Cola provided the look of Santa that we know and love is inaccurate; this look came from the robes worn by Saint Nicholas. Speaking of whom…

Saint Nicholas

St. Nicholas is often referred to as the Patron Saint of Children, but the myth stems to sainthood throughout the world – Greece, Russia and Turkey have absorbed the legend into their culture, while Nicholas has a diverse CV that also includes status as the Patron Saint of Sailors, Wolves, Shopkeepers, Bakers and Pawnbrokers.

By Аимаина хикари – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

The tradition of Saint Nicholas still exists in Germany, where he goes by Nikolaus – or Weihnactsmann (loosely translated as Christmasman, the superhero that never quite took off). Weihnactsmann visits well-behaved children and leaves them small gifts in a boot left outside their door on December 6th – though, accordingly to popular Teutonic folklore, he may be accompanied by an altogether less wholesome colleague.

Krampus

Also known as The Christmas Devil, Krampus is not somebody that you’d want to find sniffing around your chimney. A horned and fanged demon that stems from pagan legend, Krampus would allegedly beat badly behaved children with a cane on the night of December 6th – a deterrent if ever there was one. Conversely, France has a similar duo that arrive on the same night in the form of Pere Noel, a Santa-substitute that rides a donkey as opposed to a reindeer, and La Pere Fouettard (aka The Whipping Father).

The Krampus legend has grown increasingly popular in recent years with anti-Christmas types, with even Hollywood getting in on the act with a number of horror flicks that celebrate the legend of the festive scoundrel. Austria, in particular, has taken Krampus to their hearts, releasing a number of Christmas decorations and chocolates that feature his visage and characteristics. Crass commercialisation, or the demystification of a demon to avoid terrifying children? As always, it’s a matter of personal perspective – maybe we should take our cue from Scandinavia, who dealt with a similar legend.

Joulupukki

Much like Krampus, Joulupukki started life as a spooky Pagan figure of Norse mythology. Also known as The Christmas Goat, Joulupukki (the name derives from the Finnish language) would turn up at the dead of night and demand gifts from local children, though as time went on, the legend softened.

Nowadays, the myth of Joulupukki resembles that of Santa Claus almost entirely – this benevolent old man, clad in a red and white and sporting a long, white beard, brings gifts to children every Christmas Day. Where Joulupukki differs from Father Christmas, however, is in the timing and method of his arrival.

Rather than sneaking into homes via the chimney while children snooze, Joulupukki loudly announces his presence after dinner on Christmas Day and doles out presents to anyone in the vicinity – a very different approach to Italy’s Santa substitute.

La Befana

Many Christmas and Santa-centric traditions stem from Pagan beliefs, but none more than La Befana – a broomstick-riding witch that delivers gifts to children in Italy by scooting down the chimney.

Perhaps more readily associated with Halloween than Christmas, La Befana may be a little frightening to look at – and she is said to dole out solid whacks to any young person that wakes up and sees her at work, so stay in bed on Christmas Eve, bambinos – but her legend is one of altruism. So much so that La Befana is said to be a fine housekeeper that sweeps up around the chimney before departing into the night sky! She’s certainly less mischievous than her Icelandic equivalents.

The Yulemen

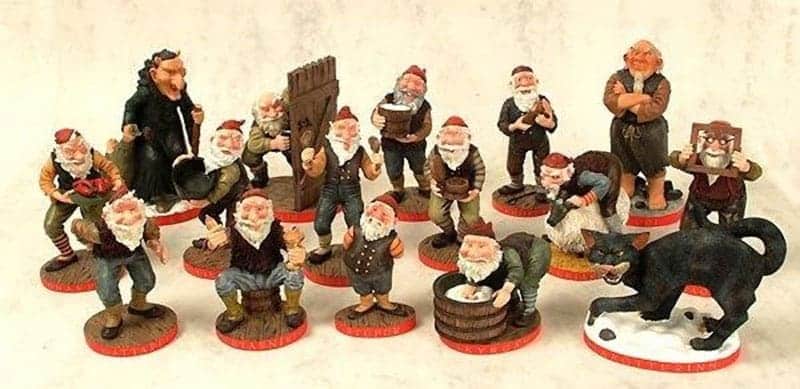

The Yulemen, or Yule Lads, are a group of thirteen gnomes that are a comparatively recent addition to festive legend, first entering pubic consciousness in the 1930s.

The role the Yule Lads play varies depends on who does the telling – some descriptions claim that these little terrors kidnap children from their beds and munch on them much as we would a turkey dinner, while others settle for tales of mischievous shenanigans and practical jokes.

Perhaps most importantly though, the Yule Lads are believed to leave gifts for well-behaved Icelandic children on each of the thirteen nights that lead up to Christmas – though those on the naughty list have to make do with potatoes.

Ded Moroz

Finally, let’s take a look at Russia’s Santa equivalent – Ded Moroz, or Grandfather Frost. The Ded Moroz legend has somewhat unsavoury origins, with the figure believed to be a malevolent and vengeful Pagan God that froze lands on a whim like some kind of psychopathic Elsa from Frozen.

By Uuuiiiccc – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Over time, however, the myth has softened to become that of a wise and kindly old man, becoming hugely popular in Russian fairy tales and nursery rhymes alongside his granddaughter Snegurka (aka The Snow Maiden).

There are number of differences between Ded Moroz and Santa, including his attire (Grandfather Frost dresses in blue as opposed to red, and carries a magical staff), location (he forgoes a station in the North Pole in favour of locating a little north of Moscow), and transport (Ded Moroz rides a traditional sled carried by three white horses, rather than a magical sleigh powered by reindeer labour). Perhaps most importantly though, he delivers gifts to children in person on New Year’s Eve as opposed to Christmas.